Vol 1 Issue 1 | April-June 2021

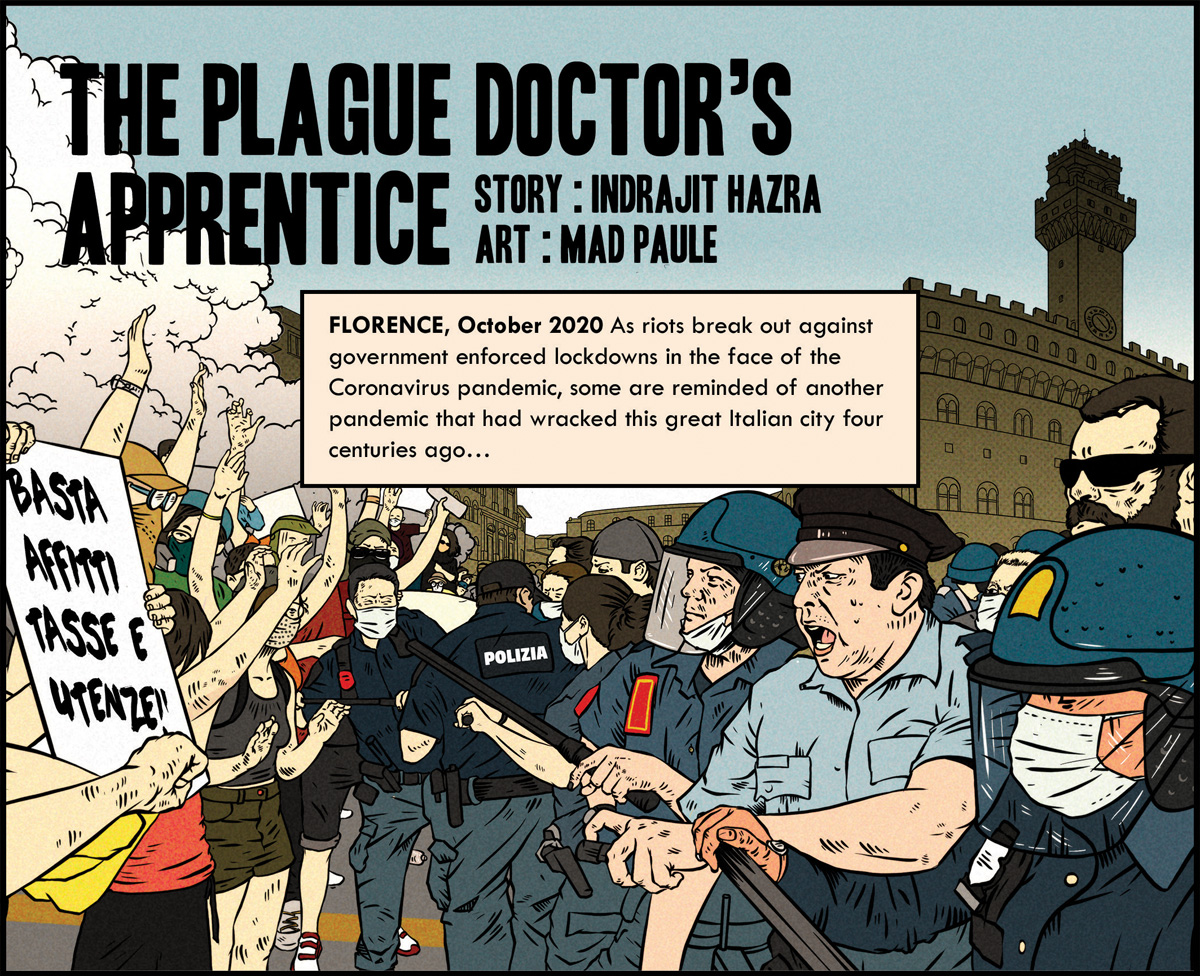

The Plague Doctor’s Apprentice

Story by Indrajit Hazra | Art by Mad Paule’

In The Plague Doctor’s Apprentice, Indrajit Hazra and Mad Paule’ have brought to life 17th century Florence as its streets are wracked by the bubonic plague. What similarities can be seen between this plague and the Covid-19 pandemic?

Of Echoes of Covid, and Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

The apprentice occupies a special place in the history of work and popular culture. The system of apprenticeship (bit.ly/3cBY11A) became developed in the late European Middle Ages (13th-15th century) in which a master craftsmen could employ young people in exchange for boarding and lodging to be trained in a craft whether it be of a baker, perfumer or a seamstress. The apprentice would aim to become a master craftsmen herself or himself – not unlike being trained under a Shaolin monk or Jedi knight.

When I first started working on this story, two famous fictional apprentices popped into my mind: Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, the hero of German writer Patrick Süskind’s fabulous 1985 novel, The Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (bit.ly/2PHL90R), and Mickey Mouse’s character in the 1940 Walt Disney film Fantasia (bit.ly/2PjjKCr), especially its most famous sequence, “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”. What had always fascinated me about both these protagonists was their journey through uncharted territory: in Jean-Baptiste’s case the art and science of making perfumes, in Mickey’s case the proto-technological terrain of magic.

But while in these two cases, mayhem is part of the ‘learning curve’ – one, dark that leads to murders, the other that leads to comic chaos – Yongle in our story is set in turmoil that is historic: the bubonic plague.

The plague that struck 17th century Italy (bit.ly/2PBc0vn) – it swept through Florence from 1629 to 1631 – was not the first to strike the region. Florence was first struck by the bubonic plague in 1347-48, which was described as The Black Death by the likes of Italian writer and poet Giovanni Boccaccio and depicted in art (bbc.in/3m2HKpr) by artists such as the Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch.

It was Orijit Sen who first suggested that I cast Yongle as a young woman (as opposed to a young man) apprenticed at the still-flourishing Santa Maria Novella Pharmacy in Florence (bit.ly/3devD4y). It made absolute sense. Yongle, whom I had named after the ‘era name’ of the founder of the Ming Dynasty in China Zhu Di (1360-1424), thus became ‘three times’ an ‘outsider’ in the story – one, as a ‘foreigner’ Italian of Chinese descent; second, as a female in a male-centric world; and third, as a young person in a world not being taken seriously because of her age.

Of course, the bubonic plague some 400 years ago in Europe, devastating lives and livelihoods, resonates with us as we live through another pandemic. And that is what we try to fill The Plague Doctor’s Apprentice with – echoes between the two ages comprising the spread of new fears, the heightening of old prejudices, attempts to find out how to stay safe, the ignorance that feeds public behaviour flouting both civic and common sense.

Remember, today we consider Science as the answer to everything – that Science will stop Covid-19 in its tracks irrespective of whether we take precautions or measures like vaccination, mask-wearing and physical distancing – and will return everything to the ‘Old Normal’. Back in 17th-century Florence, the ‘New Normal’ would go on to become the proper sanitation, hygiene and hospital healthcare that we today take for granted.

The theory of miasma (bit.ly/39rJO5n) that the Plague Doctor in the story starts out believing in to help those afflicted and keep the rest of the populace safe was also based on the science of that time – except it was incorrect. On top of it being wrong, religious leaders – in Europe, the Church – opposed any theory that challenged theirs, calling it pagan, foreign, un-Christian, anti-national.

While agencies like the Company of Misericordia (bit.ly/3u6ZbId) did sterling work and conducted great acts of human kindness in the 17th century – and even during the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918 — by taking care of plague patients, burying the dead whom no one else would touch out of fear, they were also vehicles of dogmas, notions that refused to bend to new facts – such as the Germ Theory propounded by Francesco Redi in 1668 (bit.ly/3u7jG7u).

But Science – and scientific truths – don’t appear overnight. As Isaac Newton put it in 1676 while remarking on his own discoveries in optics, ‘If I have seen farther, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants’ – discovering truths by building on building on previous discoveries. In our story, Yongle is one such fictitious, anonymous ‘giant’ on whose shoulders Francesco Redi and others like Edward Jenner, pioneer of modern vaccination, stood, discarding the earlier theory of sickness caused by ‘bad air’.

Today’s vaccines fighting the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that causes Covid-19 are created from the scientific theory that the very real Yongles in history ‘believed in’ from alternative sources in their cultures or through experimentation. Those coming in the way of safety – citizens not believing in the preventive powers of quarantine in 16th century Europe and not wearing masks in the 21st – are also worryingly real.

The plague doctor’s costume that Yongle finally dons also loops back into another standard comic book trope: the costumed superhero and superheroine – quite often with a mask. Squint your eyes, and the 2021 health worker and doctor giving you a vaccine or conducting research without a break in her or his lab wearing PPE is really the same superhero as Yongle and her 17th-century plague doctor Jedi master.