Vol 5 No 4 | Jan-Mar 2026

Flying off the Shelves

Story by Eleanor Chiari and Subir Dey | Art by Subir Dey

Our comic is set at the end of the 19th century and traces the movement of a single bird, an Asian Fairy Blue Bird, from its home in Bengal, to a lady’s hat in London, England. By focusing on a single animal, we wanted to tell a wider story about the relationship between colonialism, global trade and environmental destruction.

What was the Great Feather Craze?

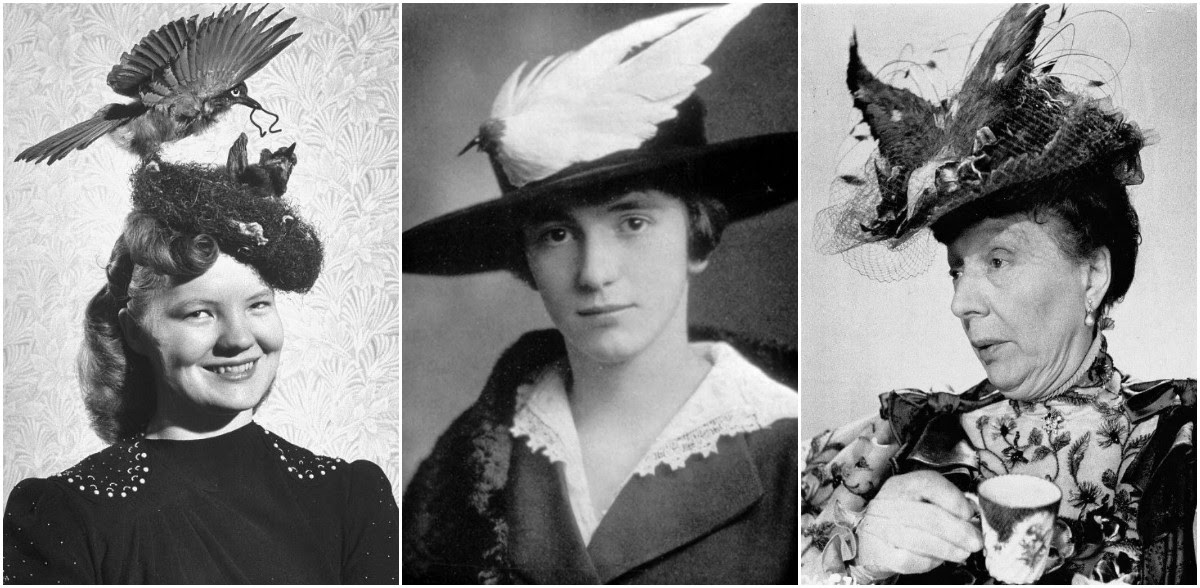

The industrial revolution and new forms of mass media (printed pamphlets and fashion magazines) created new widespread fashion trends. Between the 1860s to the 1920s, women’s fashion created a ‘craze’ for wearing feathers on hats, coats and accessories. As colonialism expanded into jungles and forests, milliners (hatmakers) began creating hats that incorporated the entire body of exotic birds, often in outlandish poses. Millions of birds were slaughtered in the process, and several species were brought to near extinction. The practice was particularly damaging because birds were killed during their mating season, when their plumage was at its most spectacular.

https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/victorian-hats-birds-feathered-hat-fashion/

How were birds hunted and traded?

Early ornithologists hired local people to find and kill bird specimens, with little pay and recognition. Bird skins were removed from the animals and preserved with a mixture of arsenic, salt, and gauze to prevent them from rotting during the journey. As people in Europe and North America saw beautiful exotic birds in natural history museums, they began to want to wear them, and feathers and dead birds became more valuable than gold.

In planning the comic, we were struck by a report from naturalist and bird defender W. H. Hudson, who visited a feather auction in London in December 1895 and noticed that in a single auction sale, “125,300 specimens” of parrots, “mostly from India” were sold. He wrote that: “Spread out in Trafalgar Square, they would have covered a large portion of that square with a gay grass-green carpet, speckled with vivid purple, rose and scarlet.” We therefore chose to show our lady wearing her hat in Trafalgar Square.

Helen Louise Cowie, Victims of Fashion: Animal Commodities in Victorian Britain (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

https://archive.org/details/taxidermistsmanu00brow/page/2/mode/2up

What about working conditions?

Working conditions in Victorian factories and sweatshops were notoriously bad, especially after gas lighting was introduced to keep workers toiling into the night. Milliners mostly employed women to put together their hats. Women were not protected by labour laws and were paid less than men. Furthermore, the chemicals used to create felt and treat fur, animal skins and dies were often highly toxic. The common expression ‘mad as a hatter’ came from a condition called erethism (also known as mad hatter’s disease), which came from prolonged exposure to mercury vapours. This condition caused physical tremors, mental health problems, as well as confusion and hallucinations.

https://youtu.be/oYV9jJzanKA?si=iUSzICwiD3zVHLLx

How did it end?

The great feather craze was so terrible that it sparked the beginning of the modern environmental movement, with naturalists and especially women activists organising to protect birds. Laws were passed to stop the feather trade, but it was ultimately the advent of the motor car and of the cinema (both highly impractical places to wear hats with big feathers) that ended the gruesome fashion.

https://www.thecollector.com/victorian-great-feather-craze-ecological-impact/

https://youtu.be/-GOTyrghhWM?si=EWF5OxB3Q1xTwia-

Fast fashion is more damaging than the Great Feather Craze

Today, fast fashion is one of the biggest threats to our planet, operating on a ‘buy-wear-toss’ model that creates a massive environmental footprint. The industry is responsible for nearly 10% of global CO2 emissions, more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined, and consumes enough water annually to meet the needs of 5 million people. Because most of these trendy clothes are made from inexpensive synthetic materials like polyester, they act as a hidden source of plastics; every time they are washed, they shed microplastics that end up in our oceans and food chains. Furthermore, the sheer volume of waste is staggering, with the equivalent of one garbage truck of textiles being landfilled or burned every single second, as clothes are often discarded after only a few wears.

WWF on fast fashion today (also impact on workers):

https://www.wwf.org.uk/articles/fast-fashion-disaster

The hidden cost of staying trendy: https://youtu.be/60MqS6nPCZo?si=VwVUktG2QbhU034S