Vol 5 No 3 | Oct-Dec 2025

Walking English Talking English

Story by Rajesh Devraj | Art by Meren Imchen

English in India: A Brief History

English first arrived in India a long time ago, with traders and missionaries in the 1600s, even before the British began ruling the country. Interestingly, English was the third European language to reach India, after Portuguese and Dutch.

Over time, English became increasingly widespread. Many Indians, like Raja Rammohan Roy, actually asked for English education, seeing it as a way to access Western knowledge and science. A very important moment in its history was in 1835, when Thomas Babington Macaulay argued for English to be the main language for education in India. He wanted to create a group of Indians who were “Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals and in intellect” to serve colonial power. This decision officially established English education and made it the language of administration and higher learning.

Thomas Babington Macaulay, author of the infamous Macaulay’s Minute

As Indians began to use the language for their own purposes, writing books in the language and expressing their own ideas, British officials did not always welcome the change. They often had dismissive and condescending attitudes towards the English spoken by Indians, calling it ‘Baboo English’. Despite their racial attitudes, the British absorbed many influences from Indian languages in their own everyday speech. That is how many common Indian words like ‘loot’ and ‘thug’ entered the English language. Other words like ‘shampoo’ and ‘dungarees’, which we barely recognize as Indian words today, also have local origins.

Illustration from F. Anstey’s Baboo Jabberjee B.A. (1897), a British satire of Baboo English

After India gained independence in 1947, English was kept as an associate official language alongside Hindi. It became an important link language for people from different parts of India to communicate with each other. This led to a process called ‘Indianisation’, where English blended with Indian languages and culture, developing its own unique style and expressions. Braj Kachru, an influential linguist, studied this process, documenting the unique linguistic features of Indian English. He challenged the Eurocentric view of English and the idea that only ‘native speakers’ set the norms, arguing for the independent status of non-native Englishes.

One key outcome of the Indianisation of English was the rise of Hinglish, a form of colloquial speech that combines Hindi and English words and grammatical elements. The term covers various linguistic practices, including lexical borrowings, code-mixing and code-switching. Its use spans casual conversations to professional settings, and is associated with a confident, youthful identity. While some deride it as mongrel speech, suitable only for gossip columns and film lyrics, Hinglish has become a key medium for communication in contemporary India, and even gained respectability in media and the arts.

Today, India is one of the largest English-speaking nations in the world. However, contemporary Indian attitudes towards English remain complex. On the one hand, English is widely seen as a gateway to social mobility and economic opportunities, associated with modernity, science, and technology. There’s also a growing confidence in Indian English as a legitimate variety of English, with many arguing it has become an Indian language. On the other hand, English is still viewed by some as a colonial imposition threatening cultural roots. It is seen as contributing to a socio-economic divide, benefiting an elite while alienating non-English speakers. Despite these mixed feelings, English is very much alive and continues to change in India, demonstrating its ability to adapt to Indian concepts and traditions.

Even AI speaks Hinglish these days!

The Real Hobson & Jobson

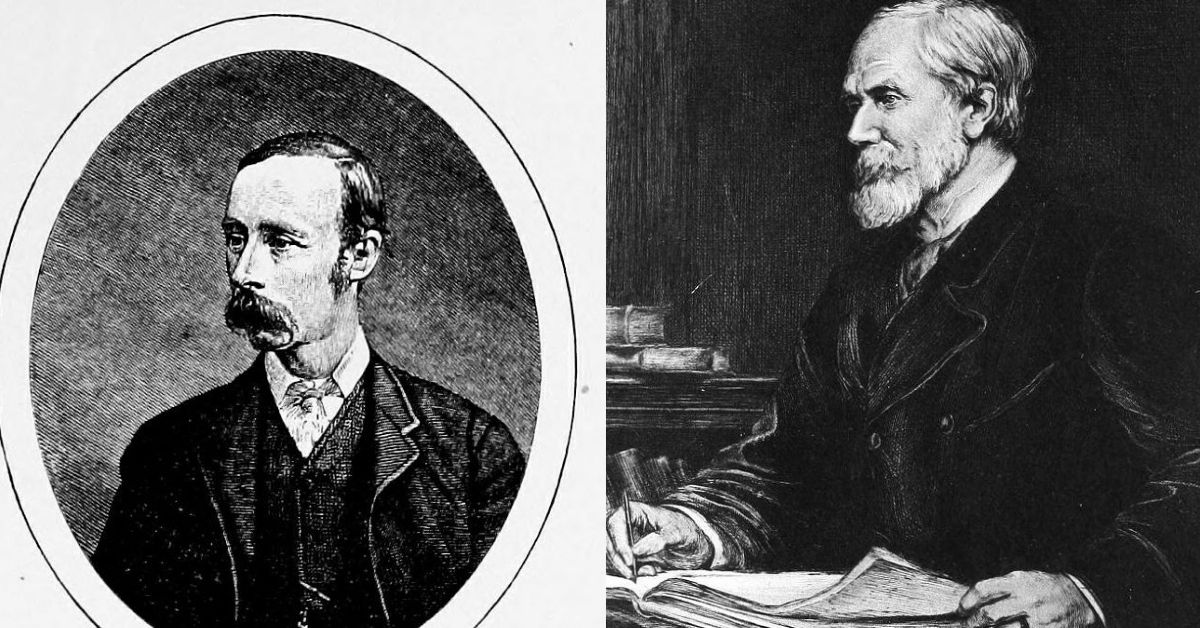

Henry Yule (Colonel, later Sir) and A.C. Burnell were the authors behind Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases (1886). Both men had extensive experience serving the colonial government in India and were serious amateur linguists. Their book is a glossary of colloquial words and phrases used by the British in India. With its scholarly yet entertaining entries on words like tiffin, veranda, chutney and bungalow, it offers a fascinating view of how deeply the English language was transformed by the colonial encounter. Each entry offers serious research, along with a very readable commentary and numerous textual quotations. Hobson-Jobson is recognized as a legendary dictionary and still remains a significant contribution to understanding the evolution of Indian English.

Arthur Coke Burnell (left) and Henry Yule (right), authors of Hobson-Jobson

Some Linguistic Definitions

The comic ‘Waking English Talking English’ uses a few specialized linguistic terms. They are defined here, along with a few others relevant to Indian English and Hinglish:

• Neologism: A new word that people create, sometimes on the spot, which might become a regular part of a language over time.

• Calque: Also known as a loan translation, a calque is like translating a phrase or idiom word-for-word from one language to another.

• Loanword: A word taken directly from one language and used in another, often adapting its sound or meaning to fit in.

• Semantic shift: A semantic shift happens when a word’s meaning changes over time, even though the word itself stays the same.

• Reduplication is when parts of a word or a whole word are repeated, often to give it more emphasis or a special meaning.

• Code-mixing is when speakers use words, phrases, or sentences from different languages together within the same conversation.

• Code-switching is when a speaker switches entirely from one language to another during a conversation.