Vol 1 Issue 2 | July-September 2021

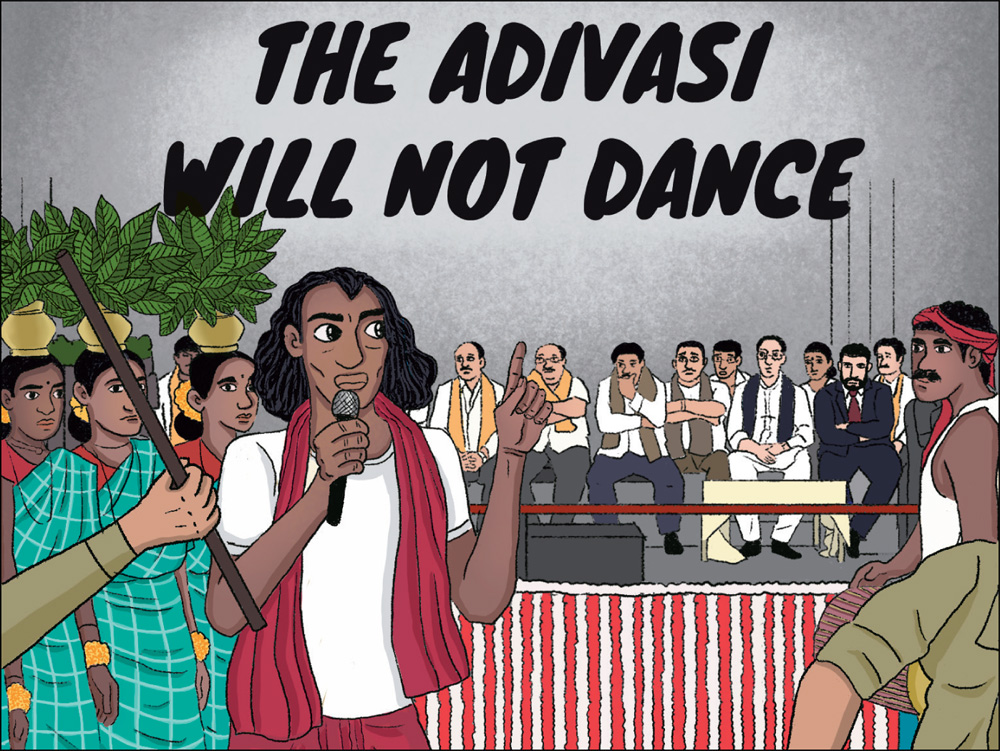

The Adivasi Will Not Dance

Story by Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar | Art by Priyanka Purty and Neha Alice Kerketta

I grew up in Jharkhand, in a place called Moubhandar, in the township of a copper mining company owned by the government of India. When I was old and literate enough to read my father’s company I-card, I learnt that he worked in the gold plant of the copper company. I was quite puzzled. How could they have a gold plant in a copper factory? And then I learnt: even though the chief mineral mined by that company was copper, there were other minerals too that were mined by the same company – minerals like gold and selenium. And that was when I realised how rich our place – then in Bihar, now in Jharkhand – was! Just 15 kilometres or so from our quarter, in a place called Jadugora, they also mined – still mining – of all things, uranium!

Coal is one of the several minerals found in Jharkhand. And, apparently, it is the mineral found in the largest quantity in Jharkhand, followed – just a little behind – by iron ore. According to the records of the government of Jharkhand, iron ore is mined in just one district in Jharkhand, while coal is mined in nine districts in Jharkhand. Pakur – the district where I used to work till about 4 years ago and where parts of my short story, “The Adivasi Will Not Dance”, are set in – is one of those nine districts of Jharkhand where coal is mined.

http://www.jharkhandminerals.gov.in/portletContent/30/40

Migration for labour is a common issue among the people of the Santhal indigenous community in the state of Jharkhand. In the present time, with better modes of transport and communication, members of the Santhal community from Jharkhand are travelling to faraway places to work [https://scroll.in/article/971171/this-worker-from-jharkhand-stayed-back-in-bengaluru-to-rescue-bonded-labourers-during-the-lockdown] but when I was growing up in Moubhandar, the name I heard most commonly of the place where Santhals migrated to work was Namal which, I was told, was the fertile region in Bardhaman district of West Bengal where the migrant Santhals worked in the rice paddies. While I was living in Pakur, I learnt of one more place where Santhals migrated to work as farm labourers: Bagri, the region between Pakur in Jharkhand and Murarai in Birbhum district of West Bengal. [https://www.asymptotejournal.com/nonfiction/shibu-tudu-memories-of-the-kirta-dangra/]

Just like in several other indigenous communities, music and dance also play an important role in the lives of the Santhals. Some of the common musical instruments played by Santhals are the following:

1. Tamak: This is the large, bowl-shaped drum played during festivals and occasions like weddings and the community hunt.

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/tamak-single-headed-kettle-drum/yAHkt6fz2WdDZg

2. Tumdak: This is a longish drum played during festivals and weddings.

https://asiainch.org/craft/musical-instruments-of-west-bengal/#!jig[1]/ML/136809

3. Banam: This is a stringed instrument, quite like the sarangi.

https://chandrakantha.com/articles/indian_music/banam.html

4. Tiriyo: This is a flute.

http://kherwalsantal.blogspot.com/2011/10/santali-musical-instruments.html

Cliched as it may sound, a Santhal village is known for its cleanliness. This might not always be the case, but, most times, this is true. A typical Santhal house in a village is characterised by an inner courtyard known as a racha. Santhal houses in villages have evolved. What used to be traditionally built with mud is now being built using concrete. The area of the racha too inside a house is shrinking. But the racha – as a singular, dominant feature of a Santhal house – remains. A useful book to know more about Santhal houses is the very interesting In Forest, Field and Factory: Adivasi Habitations through Twentieth-century India by Gauri Bharat. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/in-forest-field-and-factory/book272255