Vol 2 No 3 | Oct-Dec 2022

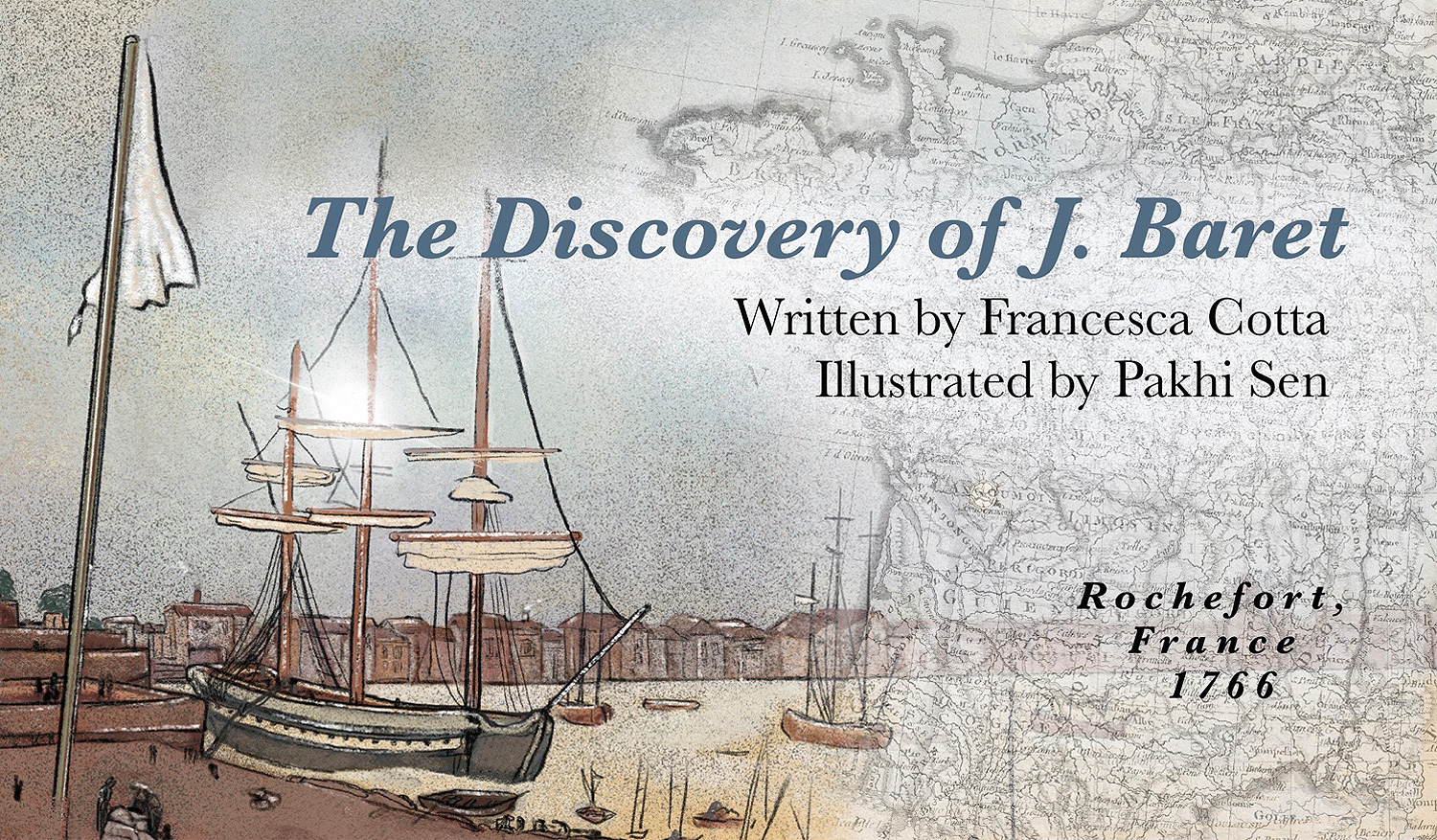

The Discovery of J. Baret

Story by Francesca Cotta | Art by Pakhi Sen

The first woman to sail the world

Jeanne Baret was the first woman known to have sailed around the world. She came on board the Etoile as the ship’s naturalist Philibert Commerson’s assistant and servant, disguised as a man because women were prohibited from sailing at the time. In keeping with her covert identity, they had to pretend to have met at the port town shortly before embarking, whereas in reality, Jeanne had been Commerson’s servant for some time. They were also lovers and it is likely that they even had a child together, but because of the class divide between them, Commerson preferred that this information be kept a secret.

https://www.npr.org/2010/12/26/132265308/a-female-explorer-discovered-on-the-high-seas

An age of discovery

The voyage that Baret and Commerson embarked on was one of the first to have a naturalist and botanist on board. Royals and aristocrats in 18th century Europe had realised the importance of the natural sciences in their colonial and trade endeavours. Assessing the resources of previously ‘undiscovered’ lands in other continents was useful to gauge their potential, first as trading hubs and then as new colonies. It was the growing sophistication of shipbuilding in Europe that made these long expeditions possible.

https://www.thoughtco.com/age-of-exploration-1435006

Contributions to science

Over the course of their South American voyage, Baret and Commerson collected thousands of specimens – over six thousand plant specimens alone! – but the labels only credit the findings to Commerson. Thanks to surviving accounts from the journals of their fellow voyagers, we know that Commerson had a leg injury that would have made moving quickly and agilely difficult. Baret’s shipmates described her as a tireless worker, conducting much of the physically demanding fieldwork of collecting specimens, sometimes by herself. One of her most notable discoveries was the brightly coloured, thorny vine that they named Bougainvillea, in honour of their ship’s commander. While over seventy specimens have been named after Commerson, it was only in 2012 that a new species of nightshade was named Solanum baretiae, in recognition of Jeanne’s impressive contributions to science.

https://www.nature.com/articles/470036a

http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/the-hand-lens/explore/narratives-details/?irn=6978

Later life

After Jeanne was found out to be a woman in disguise in Tahiti, she and Commerson disembarked in Mauritius, perhaps to spare their captain the complication of dealing with the presence of a woman on board. Jeanne continued to be Commerson’s assistant and servant until his death in 1773. Baret was able to acquire property and ran a successful tavern in Port Louis. In 1774, she married Jean Dubernat, a non-commissioned officer in the French Army. It is presumed that Jeanne and her husband returned to France in 1775. By this time, Jeanne was a person of means and was able to buy land and settle in her husband’s native village. In 1785, Baret was granted a pension of 200 livres a year by the Ministry of Marine. The document granting her this pension says of her, “She devoted herself in particular to assisting Mr de Commerson, doctor and botanist, and shared with great courage the labours and dangers of this savant.” Jeanne died in Saint-Aulaye on 5 August 1807, at the age of 67.