Vol 2 No 4 | Jan-Mar 2023

The Daughters of Relu

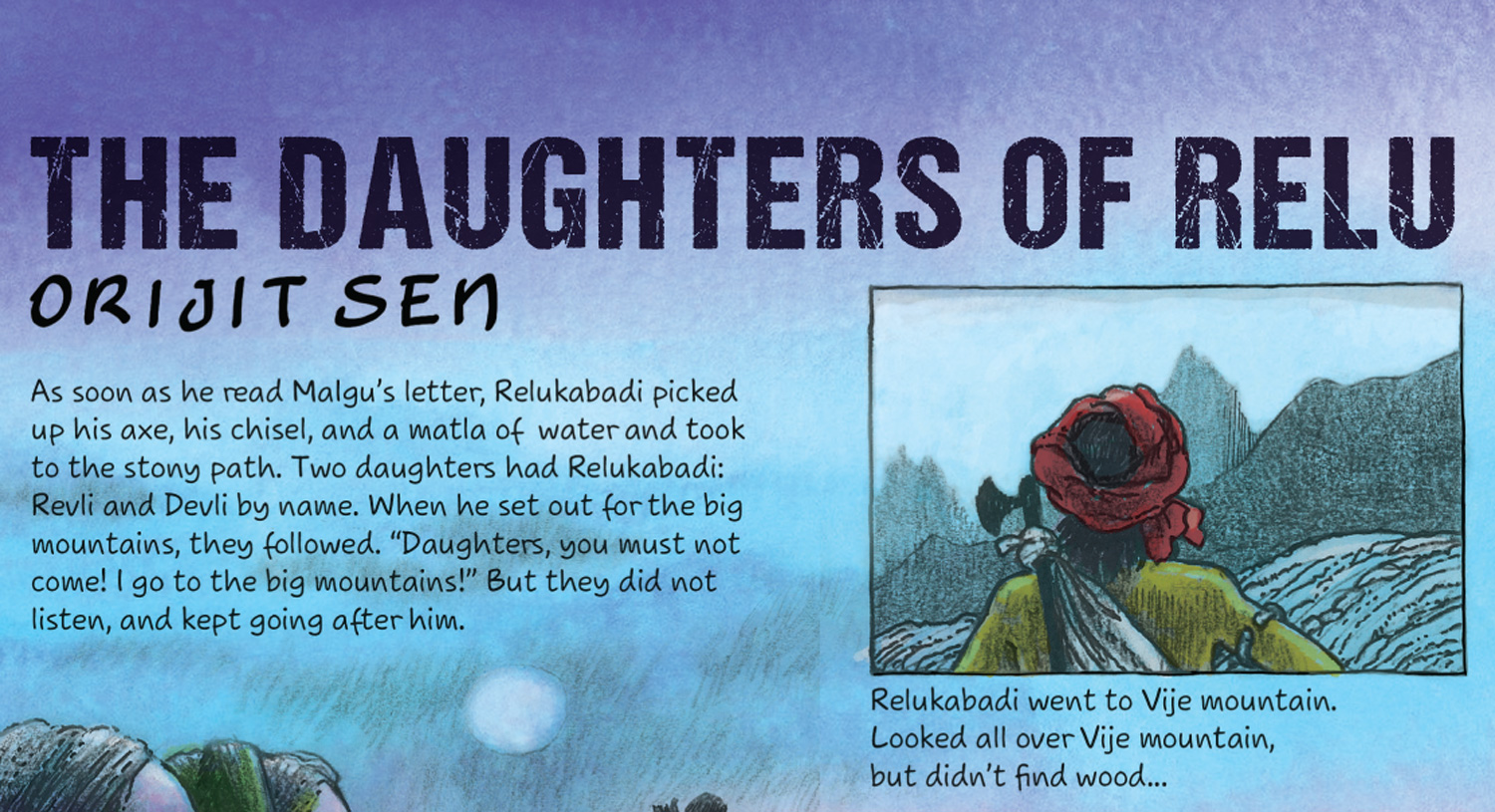

Story and art by Orijit Sen

This comic is an extract from River of Stories by Comixense Chief Editor Orijit Sen. The book is something of a landmark in the history of Indian comics, and is generally regarded as the first Indian graphic novel in English. First published in 1994 in collaboration with the environmental NGO Kalpavriksh, it tells the story of the people affected by the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam on the Narmada river. Though it wasn’t a great hit when it first came out—Orijit says, “it was printed, and promptly sank like a stone”—it gained a cult following over time. A new edition was published by Blaft Publications in November 2022, and has been doing resoundingly well.

The comic uses the creation myth of the Bhilala tribe—whose members are among the large numbers of people displaced by the rising waters upstream of the dam—as a binding element of the story. The pages reproduced here—specially coloured by Orijit for Comixense (the original book is completely in black-and-white)—provide a glimpse of that background tale, and lead into the contemporary world of the Narmada Bachao Andolan. Orijit joined the Andolan in the early 1990s, and immersed himself in that movement in order to tell its tale as deeply and authentically as possible. Over the three years that it took him to write and draw the book, he travelled back and forth between Delhi, where his studio was located, and the length and breadth of the Narmada Valley.

The Sardar Sarovar Project

The Narmada Valley Project was planned in 1946, in the Nehruvian era when big dams were seen as both a marker and a means of progress. But it was only in 1978, when the Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal gave its final orders, that work on the project started. While a number of dams of small, medium and large sizes were envisaged, it was the Sardar Sarovar Dam in Gujarat that attracted the most resistance. That was because its planned 138-metre height would lead to the submergence of 38,000 hectares of land, displacing more than 250,000 people from 244 villages.

In 1985, the environmental activist Medha Patkar petitioned the Supreme Court on behalf of the affected people. The Supreme Court stayed the work till proper rehabilitation plans were drawn up. In 1993, the World Bank, one of the prime funders of the project, withdrew its Narmada loan, and published an independent review critical of the project. In 2000, the Supreme Court allowed construction on the dam, making supervised rehabilitation a condition.

After the Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power at the Centre in 2014, the tide turned in favour of big development projects with reduced emphasis on their effects on the common people. Just 17 days after the new government took over, Modi granted permission to raise the dam to its full height. Despite rehabilitation being still incomplete, the dam was inaugurated by the Prime Minister in 2017.

The Narmada Bachao Andolan

The Narmada Bachao Andolan is one of the largest people’s environmental movements in the world ever. Its core is the large population of people affected by the rising waters upstream of the Sardar Sarovar Dam—many of them Adivasis. Spearheading the movement and giving it a voice has been Medha Patkar. The Andolan has also drawn NGOs and environmental activists from many places, including several from outside India. At various points of time, social reformer Baba Amte, writer Arundhati Roy, and musician Rahul Ram have been closely associated with the movement.

Though the dam is now built, the Andolan continues its struggle, trying to secure the rights of the people who have been affected, many of whom have neither been adequately compensated nor rehabilitated as per promises made.

“Our little river” by Rabindranath Tagore

Rivers are so deeply part of the heart and soul of our country, they appear in every medium of expression, particularly in poetry and song. Here is a beautiful poem by Rabindranath Tagore that evokes the picture of the river as the lifeblood of rural Bengal.

| Amader chhoto nodi Amader chhoto nodi chole bnāke bnāke Boishakh maashe tay hnatu jol thake. Paar hoe jay goru, paar hoy gaari – Dui dhaar unchu taar, dhalu taar paari. Chik chik kore baali, kotha nai kada; Aar paare aam bon, taal bon chole- Shokale bikale kobhu nawa hole pore AshaRe badol naame, nodi bhoro-bhoro- Dui kule bone bone pore jay shara, |

Our little river Our little river flows gently curving In Baisakh, her waters barely reach the knees. Across go cattle, across go carts – The banks rise high, but they cross with ease. The glittering sand shines, no mud to be seen; On this bank, mango and palm trees sway, And any time that it catches their fancy In Ashaad, the monsoon swells the river’s flow On both banks, the denizens revel in glee |