Vol 1 Issue 2 | July-September 2021

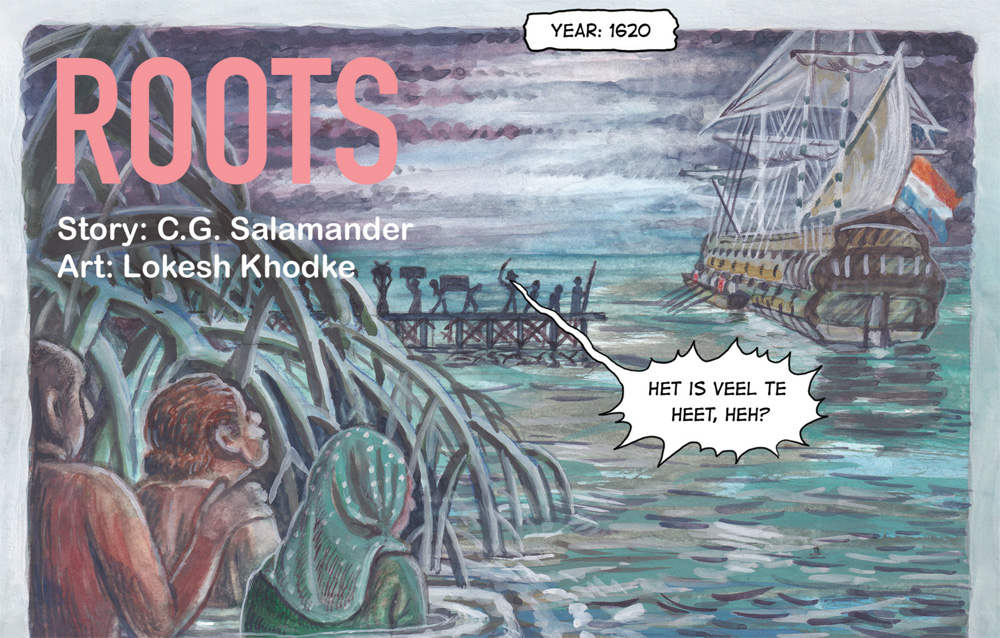

Roots

Story by CG Salamander | Art by Lokesh Khodke

Uprooted

There’s this story about my great grandfather. When he was fourteen or perhaps fifteen, he was tied to a tree and beaten within an inch of his life, all because he wanted to do away with his last name. Left there for an entire day, he would have died had his grandmother not untied him under the cover of night, given him what little money she had saved, and ordered him to flee.

Meanwhile, in the villages surrounding Pulicat lake, the people who inspired the story “Roots” were undergoing a displacement of their own. As it happens with many who are displaced, they had been kicked out of their ancestral lands in the country’s relentless pursuit of development. The people of Pulicat now fight against a bigger, more dangerous threat using conservation and environmentalism.

The Dutch and the VoC

Before the Vereenigde Nederlandsche Oost Indische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company), Pulicat was filled with mangrove forests. As a matter of fact, Pazhaverkadu, the original Tamil name for the town, roughly translates to forest of the rooted fruit. The Dutch however cleared large sections of the mangrove forests to build their fort Geldria (parts of which can be found today, hidden amongst the bushes and in complete ruins).

The Dutch first arrived in India and made Pulicat their own after ousting the Portuguese around the dawn of the 16th century. Like most colonial powers, they had originally come to trade spices, textiles, and precious stones. But as their trade began to flourish, they made themselves more at home, and began to focus on governance. The Dutch built their fort in 1613 and a few years later set up gunpowder factories and expanded their armies to strengthen their stronghold. They were so successful that the most common languages spoken in Pulicat during the time were Dutch and Tamil. During their occupation of Pulicat, the Dutch mainly traded in diamonds and indigo, but as time passed, the VoC began trading people.

https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/the-dutch-connection/article4873212.ece

Slaver’s Bay

There is very little to go by regarding the Dutch slave trade, apart from the extensive records that the VoC kept. The slave trade in Pulicat was rampant – people were carted away by the thousands. As a matter of fact, the ‘master list’ of slaves transported in VoC ships through the Bay of Bengal totals 26,885 men, women and children.

The Dutch employed brokers to catch and bring them slaves, and would pay anywhere between 4 and 40 guilders for each captive. The slaves were dressed in white cotton clothes and shipped to Indonesia to work as agricultural hands or as skilled labour. Slaves from Pulicat were important to the Dutch because the slaves transported from African colonies rarely survived the long and perilously unsanitary journey.

The slave trade continued well into the late 1700s, lasting almost 200 years. There are even accounts of secret slave trades being carried on despite being banned by the British East India Company.

The Pulicat Wetlands

It’s been over 200 years since the Dutch left, and Pulicat is still under the threat of ‘development’. From forts set up by colonisers, rocket launch sites set up by the Indian government, and mega ports built by large corporations, the wetlands around Pulicat have constantly been in danger.

This region is of special importance because the rivers that drain into the Ennore Creek and Pazhaverkadu lagoon create an important biodiverse mosaic of ecologies – riverine systems, floodplains, tidal flats, salt pans, mangroves, tropical dry evergreen forests, backwaters, coastal sand dunes, sandy beaches. You’ll find them all here. The lake and its wetlands are also home to a wide variety of migratory and resident birds, such as pelicans, herons, egrets, storks, flamingos, ducks, shorebirds, gulls and terns.

Tidal Bores and Tsunamis

Biodiversity aside, what makes Pazhaverkadu so special is that it happens to be Chennai’s largest flood catchment area and cyclonic buffer zone. What this means is that Pazhaverkadu is single-handedly responsible for reducing Chennai’s flooding by a significant margin. Considering that Chennai is a city that experiences biblical floods every time the sky sneezes, it isn’t hard to see how 10 lakh lives would be directly affected by the flooding should the wetlands and the mangrove forest suddenly disappear.

https://sanctuarynaturefoundation.org/article/a-pulicat-story%3A-the-lagoon-that-protects-a-city

Mangrove Forests

Mangroves are plants that grow in thick clusters along the shores. They are salt-resistant trees or bushes that grow in clusters, and have a thick tangle of roots that prevent the waves from washing away the sand from the coastline. The plants and trees that make up the mangrove forests shed their leaves to get rid of their excess salt, which is in turn eaten by aquatic life, while their thick roots provide smaller, infantile fish and sea creatures with refuge in the form of a natural nursery.

There are more than 60 species of mangroves, and they can be found all over the world. Mangroves can be short bushes or they can be trees that are several feet tall. But the importance of these trees and their usefulness to the environment, especially flood prevention, has been greatly underestimated. Large sections of mangrove forests in Pulicat and around the world have been cleared for human use, leaving the wetlands and the places surrounding them vulnerable to flooding.

Mangrove Protection and Conservation

But thankfully all is not lost. The people of Pulicat and its surrounding villages have rallied to fight for their land. Victims of displacement themselves, they’ve witnessed history repeat itself far too many times, and have now taken it on themselves to save their land.

Resorting to protests, activism, and conservationism to fight for their lands, they’ve repopulated their wetlands by setting up nurseries to grow mangrove saplings, by selecting the right mangrove tree to be grown, and by planting the saplings in canals and enabling them to self-propagate. Mangrove conservation however, is a painstaking process that requires patience and a strong will, owing to the large number of trees that are lost to the tide.

A Festival of Flamingoes

The restoration of mangrove forests automatically results in the formation of natural nurseries for smaller aquatic life to breed. More aquatic life means more fish and prawns, and more fish and prawns automatically means that more migratory birds have reason to stop by.

Threat of Port

A proposed Adani megaport in the region would pose a direct threat to everything discussed above. It would weaken the natural flood catchment and leave the surrounding towns and cities more vulnerable to floods, it would destroy an entire ecosystem, destroy the habitat of a list of animals and birds, and would cause the livelihood of lakhs of people who depend on the backwater for their livelihoods.

But more importantly it would displace people on a large scale and cause an ugly history to play out once again.