Vol 1 Issue 3 | October-December 2021

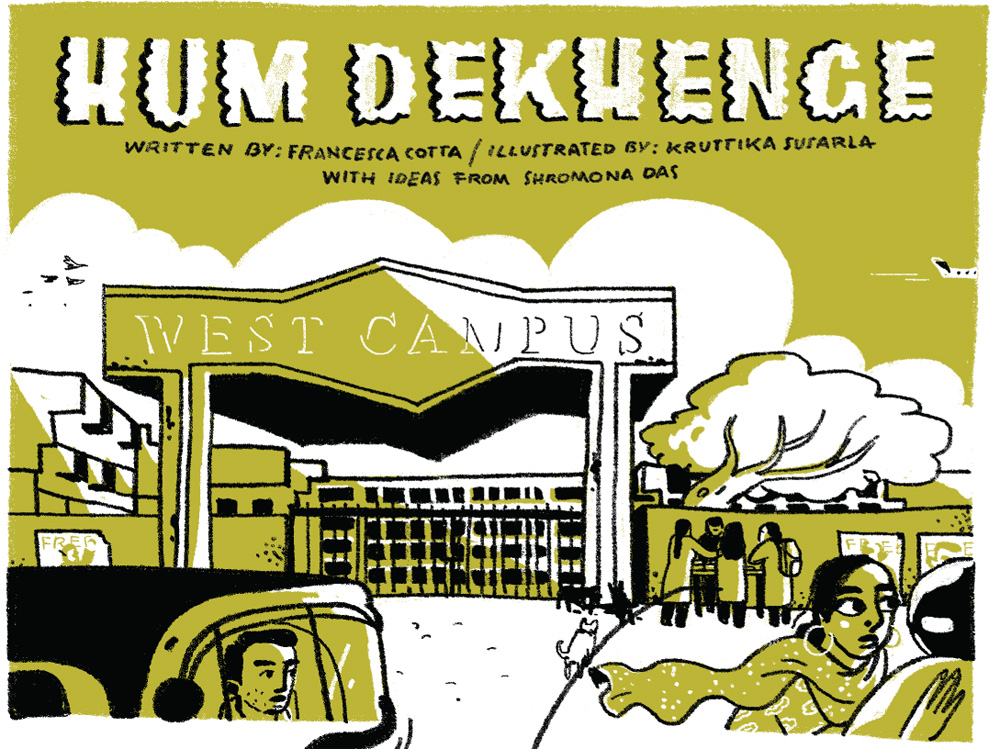

Hum Dekhenge

Story by Francesca Cotta | Art by Kruttika Susarla

Hum Dekhenge

In 2013, I left my home in Goa to attend college in Pune. As with most of the first-year students, my parents found me a hostel in the vicinity of my new campus. The girls’ hostels in the area had much earlier curfews than the boys’ hostels did. But the hostel I was living in was notorious for having the earliest curfew among them all. There were many strict and baffling rules to be followed. For example, we were once warned not to wear shorts inside the premises of the hostel ‘in case people happened to look in’. After all, we didn’t want to give the hostel a bad name, did we?

My roommate and I would often look out of our barred windows, onto the drab grey compound wall fortified with shards of broken glass, and make grim jokes comparing the hostel to a prison.

In 2015, when a wave of Pinjra Tod protests began to ripple across India, I felt a strong sense of solidarity with the protestors and an even stronger sense of regret that the movement hadn’t begun two years prior, when I could have used some more freedom from the stultifying conditions I’d been living in. That aside, I’m glad that the movement has only picked up momentum since then, but there’s still a long way to go for young Indian women to enjoy equal freedom and unconditional safety in and around their campuses.

Pinjra Tod

Pinjra Tod is a protest movement that began in 2015 in Delhi, in response to patriarchal, restrictive regulations for women students in hostels and paying guest (PG) accommodations. The movement has since spread across the country, and seen participation from students of a number of colleges around India.

Read more about the movement here: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-34486891

Hum Dekhenge

“Hum Dekhenge” (“We shall see”) is a famous Urdu poem by the Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz. Originally written in 1979 in reaction to the oppressive rule of Pakistan’s then President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, it has of late become a powerful protest song in India, starting with the 2020 anti-CAA-NRC demonstrations. The poem has been translated and performed in several Indian languages.

Watch/listen to one rendition of the song here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bIWbO-6I7r4

Why protest?

Contrary to what some may espouse, the right to protest is vital to a healthy democracy. As per Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India, ‘Freedom of speech and expression’ is a fundamental right given to its citizens. This includes the right to hold peaceful public demonstrations, and to speak up against the state when necessary.

Historically, protests have often inspired positive social change and the advancement of human rights. They aid in the creation of an aware and engaged citizenry. Through direct participation in public affairs, protests enable individuals and groups to express dissent and grievances, to share their opinions, to point out flaws in governance, to demand that the authorities rectify problems, and to hold them accountable for their actions and decisions. This is especially important for marginalised groups, whose interests are otherwise poorly represented in society.

Youth protests in the internet age

From Lebanon to Hong Kong, from the UK to India, the internet – in particular, social media – has enabled large scale, youth-driven, peaceful protests across the world for about a decade now.

Social media has emerged as a powerful tool to spread awareness about important social and environmental justice issues that directly affect the future of young people today. It is also a convenient way for strangers in far-flung places to discuss issues that they have in common; whether of local, national or international relevance.

It has also proven to be a handy tool for disseminating announcements about on-ground protests and other forms of civic organizing. In light of the Covid-19 pandemic making social distancing the norm and public gatherings difficult in large numbers, many young people have begun using social media and other digital communication tools to take their protests online.